Activist

Stepping beyond the role of interpreter

I’m no conduit

Within an hour of starting my Spanish-English medical interpretation course, I knew I would never ever become a medical interpreter. To be fair, being a medical interpreter was not my goal in the first place. I just wanted to develop skills for my work connecting Spanish-speaking youth and families with the outdoors and nature.

The training was great – easily one of my favorite adult professional development experiences. During it, I daydreamed a little about what it would be like to be an interpreter for high-level politicians much like Nicole Kidman in the movie by the same name, but with less of me being embroiled in a plot to kill a president and more of me saving the day through my amazing language skills.

But my skills aren’t good enough. Even though I surely could have mastered medical vocabulary, I knew I would never be able to fulfill the high-stakes responsibilities for medical interpretation. It would simply require too many life-or-death decisions hanging on my ability to accurately render other peoples’ words, feelings, and thoughts.

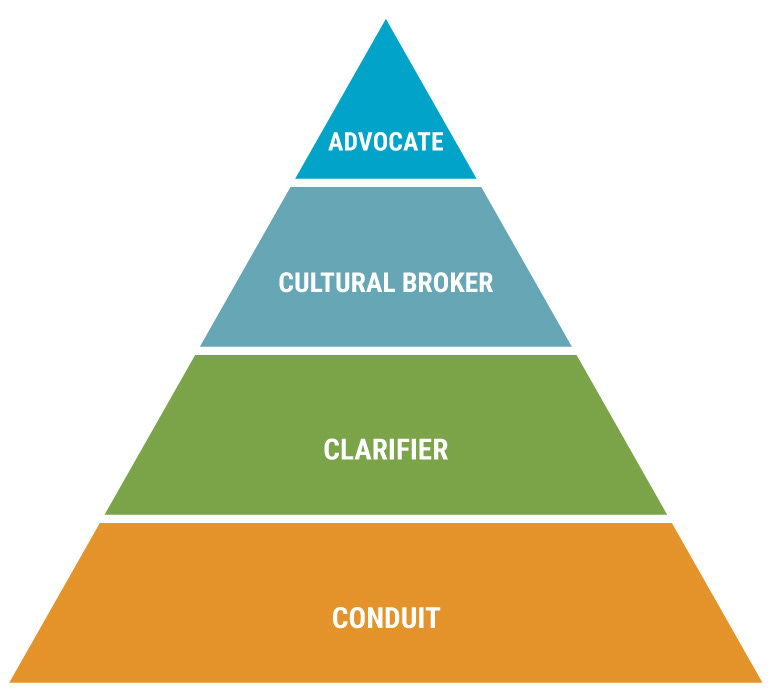

And there’s another reason too. Let me explain using this pyramid depicting the roles of an interpreter:

At the bottom we have “interpreter as conduit.” This is when the interpreter hears words, pipes them through their brain, and spits them out in a new language, passing along a message. Apps and bots can do a solid job with conduit interpretation.

Next, we have the clarifier role. Like it sounds, an interpreter taking on this role would intervene when they believe a word or phrase needs clarification to be understood. They might ask a clarifying question or add a short explanation to ensure the medical provider or the patient truly understands the other party. After finishing clarification, the interpreter drops back into the role of conduit.

Climbing higher on the pyramid, we have the role of cultural broker. An interpreter might don this hat if they believe different mores and values between the patient and the medical provider – or between a patient’s culture and that of western medicine – are inhibiting communication. There were tons of interesting examples in our course curriculum. I remember a story of an interpreter explaining the healing interventions performed by a Hmong shaman on his Hmong patient and then turning to share why the White doctor, coming from western medicine, had a different approach. This level of interpretation seemed essential and beautiful – and totally beyond my reach.

It made me wonder how anyone can interpret if they are not born to or deeply immersed in two languages and two cultures – like someone who grows up speaking English at school and Spanish at home with their Mexican immigrant family. This person would probably be a great cultural broker for Mexican patients in the U.S. medical system – but what would happen if the patient was Cuban? Or Spanish? These are cultures with which the interpreter would have considerably less fluency.

I miraculously graduated from high school with a remarkable degree of Spanish language proficiency. Señora Kottwitz (after whom my daughter Nora was named) was the best teacher I ever had. And, despite Señora’s efforts to introduce us to both language and culture, my northern Wisconsin upbringing means my cultural fluency in any Latin American or indigenous culture is insufficient to represent how cultural beliefs play into conversations about health care. Even in Bolivia where I studied abroad in college, my cultural awareness seems inadequate for working at this level.

Up at the tippy top, we have the role of advocate. An interpreter acting as an advocate moves way beyond words-in-words-out.

According to the National Council on Interpreting in Health Care1, advocacy is: taking action or speaking up on behalf of a service user whose safety, health, well-being or human dignity is at risk, with the purpose of preventing harm.

Advocacy is understood as an action taken on behalf of an individual that goes beyond facilitating communication, with the intention of supporting good health outcomes. In general, advocacy means that a third party (in this case, the interpreter) speaks for or pleads the cause of another party, thereby departing from an impartial role.

The advocate role is a hot topic and presents serious ethical dilemmas to interpreters whose assigned job is to facilitate communication. As such, the role of advocate is considered to be stepping beyond pure interpretation.

One interpretation textbook I found said, “only exceptional circumstances can justify advocacy on the part of the interpreter.”

With that, any remaining interest in being a medical interpreter went out the window. And, frankly, any interest in “interpreting” – at least by definition – fell away.

Cultural Broker-Advocate

Impartiality is not for me. I can see the value – and I’m grateful others can do this – but I have lots of opinions and I have an agenda. I’m the fiercest of advocates for mainstreaming apple-a-day nature-based learning in schools everywhere. It’s good for kids, it’s good for teachers, and it’s good for the planet.

I work with teachers in schools. Having been a high school Spanish teacher, I feel deeply familiar with teacher and school culture. I was also an outdoor educator for the better part of two decades. When I describe the Teaching Students Outdoors workshop, I often say that it’s about translating indoor teaching methodologies (which are practiced indoors by default, not because they have to be!) into an outdoor space, empowering teachers to use their own skills within their own profession to successfully adopt outdoor nature-based learning into their own expertise and practice. In the workshop, we do several translation activities – mapping indoor classroom management practices to an outdoor classroom environment and framing risk management outdoors by contextualizing them with risk management skills teachers use everyday indoors.

Way beyond conduit or even clarifier (though I do some of that too), I spend most of the training as a cultural broker, interpreting between the languages and cultures of learning outdoors and classroom teaching by using the words from both languages and providing cultural context for each. And I advocate for adopting nature-based learning in routine teaching practices. I am not impartial.

Activist

When I step out of workshops with teachers and talk with people – educators and non-educators – in the wider world, I’m an activist, which probably sits as a star on top of the pyramid.

Not to get too Loraxy here but when I work on integrating routine nature connections in schools, I sometimes feel like I “speak for the trees, for the trees have no voice.” Because if we don’t recognize the personhood – or at least inherent right to exist – of more-than-human nature, we won’t take care of it. And we won’t even see more-than-human nature if we don’t have a chance to grow connections and community with it.

I’m speaking for the kids, too, who I believe have a fundamental right – and a need – to develop emotional connections with more-than-human nature. And also a right to feel good and to learn and experience joy, all of which are supported by nature-based learning.

And for the teachers. They have voices but we (many of us!) aren’t listening. We can’t hear them over all of the yelling and bickering and rancor. And they also deserve to feel good and experience joy. And nature-based learning helps with that too.

Before I left Kenya to return to Colorado and Wisconsin for two months, I visited Sister Mninga, the remaining stump-body of my tree neighbor who has been talking to me ever since she was felled in February. I pressed my hands to her flesh and listened. She told me that I am a messenger. I need to keep talking (and listening!) until everyone feels this message: students, teachers, and our planet NEED nature connections. These can happen in schools through apple-a-day nature-based learning.

❤️,

B

As cited in this textbook for medical interpreters from Cross Cultural Communications.

I like the bleeding stump and still wonder why the tree was sad